2023-10-27T08:57:00

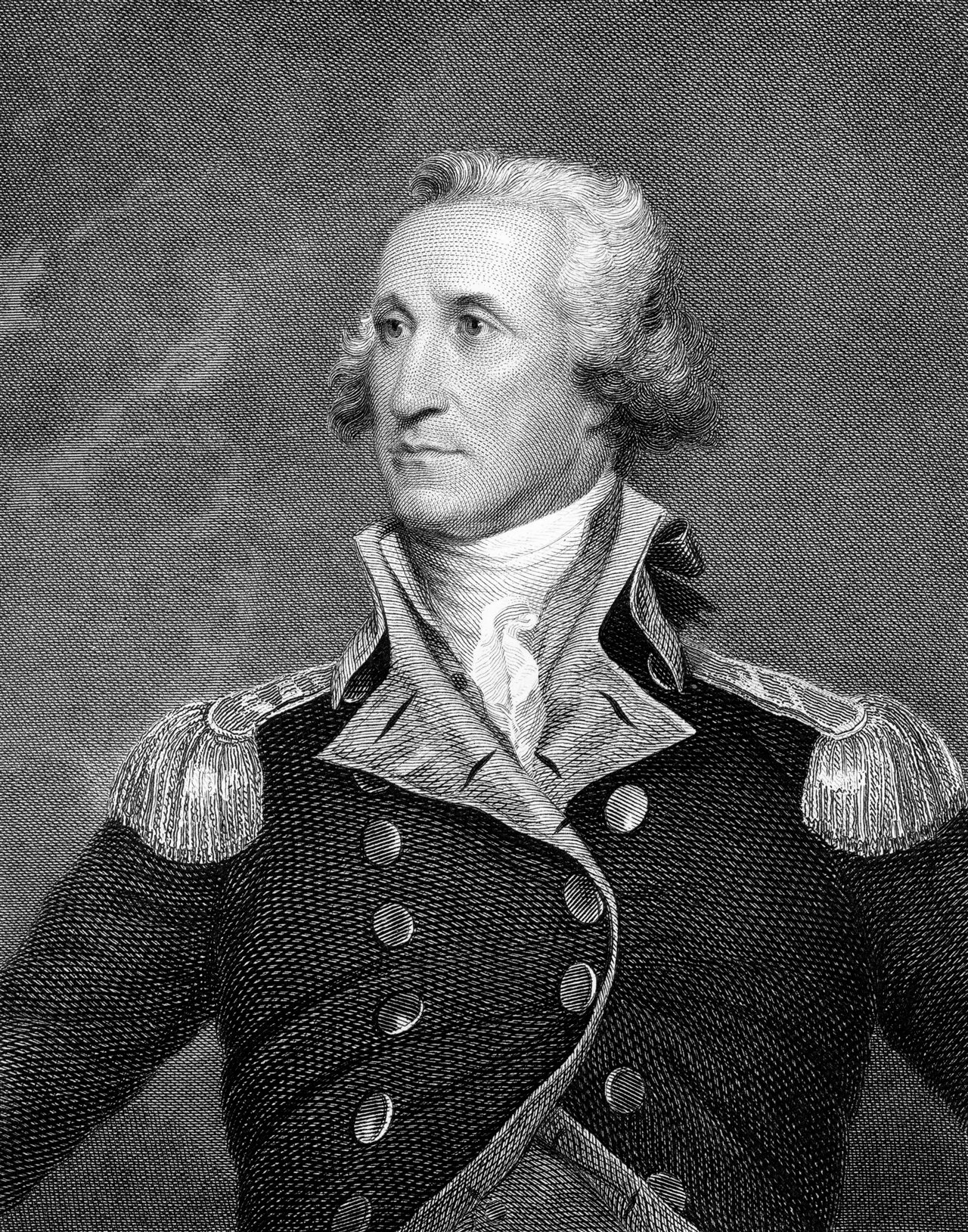

(BPT) – George Washington was indispensable in the Revolution. Without him, the army may not have achieved victory. Moreover, his willingness to repeatedly give up power — including the return of his commission to Congress and later stepping down as President — makes him one of the most laudable figures in world history.

Yet, Washington made some catastrophic blunders:

- His army was almost captured in New York at the beginning of the Revolution.

- He alternately supported and then squandered opportunities to take Canada.

- He allowed his southern army to be isolated and captured in Charleston.

- He appointed Benedict Arnold as the commander of American forces in Philadelphia.

This last act, as much as any other, could have meant the failure of the Revolution and Washington’s death.

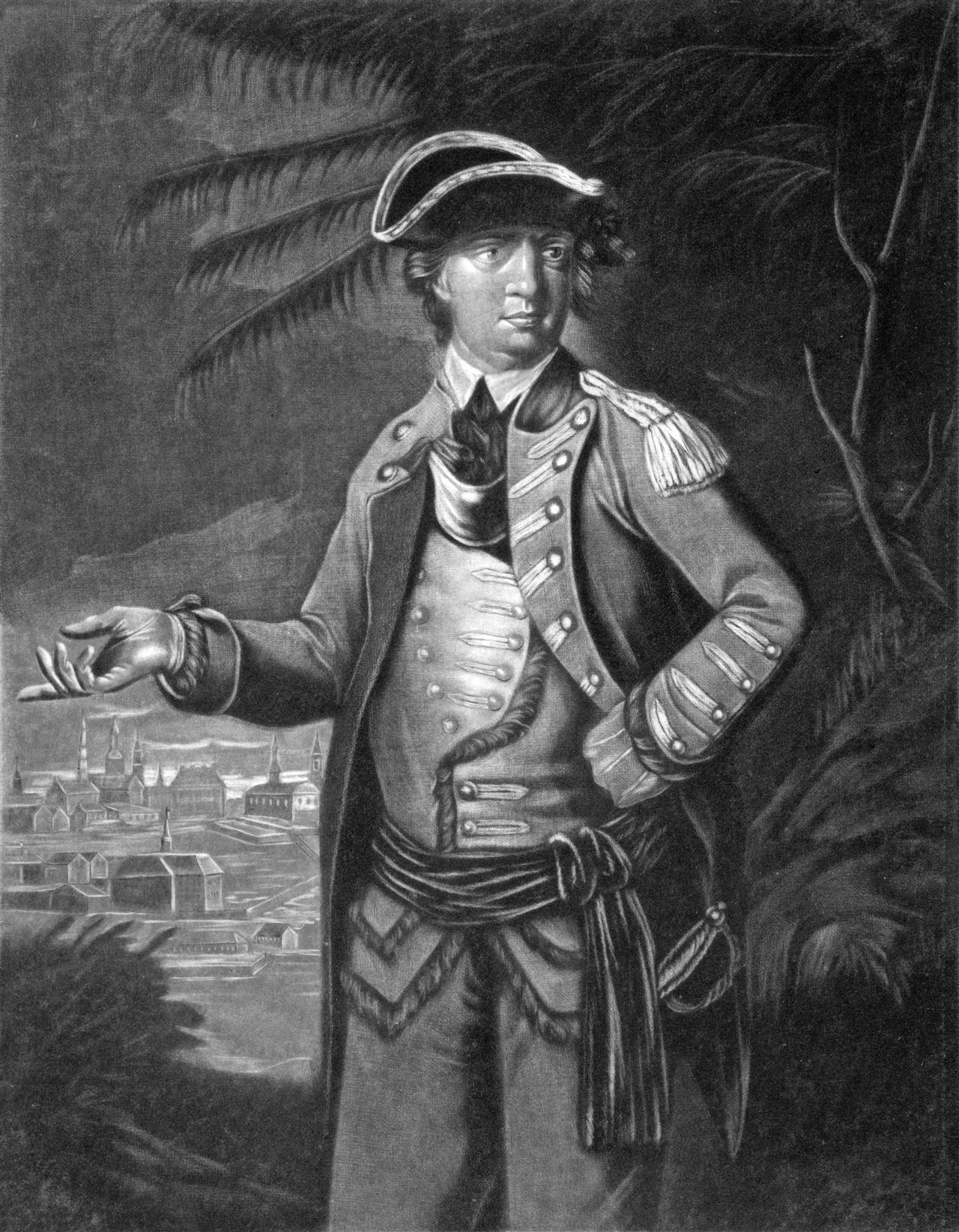

Benedict Arnold

Stephen Yoch’s new book, “Becoming Benedict Arnold,” describes the Revolution from Arnold’s point of view. One part of the book explores Arnold’s experience being severely wounded at the Battle of Saratoga, where his femur was crushed under a horse as he secured victory for the Americans.

Washington knew Arnold could not continue to serve as a battlefield commander because of his injuries, so he put him in a position providing administrative leadership as a respected member of the commanding general’s inner circle.

On June 18, 1778, after almost nine months of occupation, Sir Henry Clinton and 15,000 British troops evacuated Philadelphia. Washington saw the opportunity to reward Arnold for his service and provide stability to a divided city. Philadelphia had been brutalized by the British and its population was traumatized. Loyalists left behind after the British exodus were targets of their vengeful wrath.

Washington’s massive mistake

Yoch explains that the decision to put Arnold in charge of Philadelphia was one of Washington’s worst decisions. Arnold was given the impossible task of treating all sides fairly and preventing the radicals from exacting retribution.

Even an extremely experienced politician would have been stymied by this objective, but Arnold was especially ill-suited. He saw his tenure in Philadelphia as an opportunity to make money by engaging in questionable business activities while recuperating in comfort. Arnold also ignored the political implications of entertaining young women who had prior shown loyalist sympathies, or using fine carriages previously driven by the British oppressors.

Joseph Reed was a former aide of Washington’s who had betrayed him and was dismissed. Reed viewed Arnold as a Washington surrogate, a likely member of a junta that would follow Oliver Cromwell’s example of ruling America following the Revolution.

The fact that Arnold had been wounded multiple times serving the Cause did not dissuade Reed and his cronies from labeling Arnold a monarchist and a traitor to the Revolution. Reed and his men ultimately commenced a legal action against Arnold in which he was court-martialed and admonished.

Meanwhile in Philadelphia, Arnold fell in love with loyalist Peggy Shippen, who connected him with Major John André, the head of the British spy network. The abuse Arnold suffered at the hands of the Philadelphia radicals pushed him directly into the arms of the British.

Arnold and André hatched a plan to turn over West Point and engineer the capture of Washington and his senior staff. The Revolution was saved by sheer luck and Arnold’s plot was foiled.

Washington’s decision to appoint Arnold to Philadelphia led Arnold to his treason and could have meant the end of the Revolution. Once again Washington’s luck, or as he would say, “the hand of providence,” saved him from his worst mistake.

For more information and to order “Becoming Benedict Arnold,” visit Amazon.com.